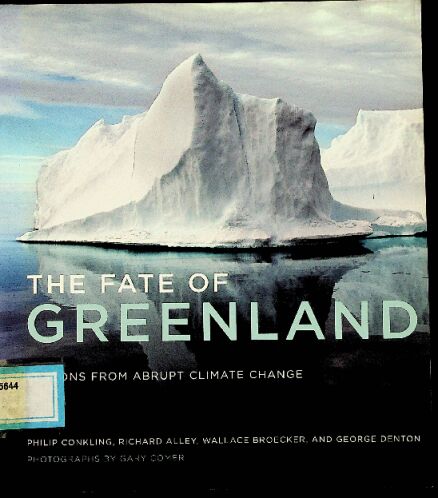

书名:The fate of Greenland

责任者:Philip Conkling | Richard Alley | Wallace Broecker | and George Denton ; photographs Gary Comer. | Denton, George H.,

ISBN\ISSN:9780262525268,9780262015646

前言

The above comments were among the first lim-nological observations made in Antarctica. The ear-lier British Discovery Expedition, in 1901—1903, alsoled by Robert Falcon Scott, made the first measure-ments of lake level in Lake Bonney and measuredthe distance across the narrows between its eastand west lobes. These were important data againstwhich present water levels can be compared. Infact there has been a very significant increase inthe depth of the McMurdo Dry Valleys lakes since1903, indicating that ablation does not balance in-flows from the glaciers. These observations weremade during the age of Antarctic exploration. Itwas not until the International Geophysical Year(1957—1958), the establishment of the InternationalCommittee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), and theestablishment of permanent research stations in the1950s and 1960s, that Antarctic limnology reallystarted to gain momentum.

Antarctica contains the most diverse range oflakes on the planet. There are many freshwater andbrackish to hypersaline lakes in the ice-free areas,but there are also freshwater epishelf lakes that ei-ther overlie seawater or have a connection to thesea and are therefore tidal, cryolakes on glaciers, iceshelf ponds and lakes, and most remarkable of all,a vast network of subglacial lakes under the conti-nental ice sheet, of which lake Vostok, Whillans, andEllsworth are the best known. The latter confrontscientists endeavouring to unravel their secrets withmajor challenges, and effectively represent the mod-ern equivalent of the age of exploration.

There are a number of excellent books that dealwith the limnology of specific areas of Antarctica,for example Ecosystem Dynamics in a Polar Desertedited by John Priscu and The Schirmacher Oasisedited by Peter Bormann and Diedrich Fritzsche,but there is no single volume that pulls togetherthe data for the entire continent. Our aim was toproduce a book that would be of general interestto those with a limited knowledge of Antarcticlakes, as well as a reference book for experiencedresearchers in the field. The first chapter is intendedas an introduction to Antarctic lakes, while subse-quent chapters provide an in-depth considerationof specific lake types. The final chapter considersfuture directions.

There are still major gaps in our knowledge ofAntarctic limnology, as this volume will show, butnonetheless the expanding database provides uswith a clear picture of the formation and ecologyof some of the most extreme water bodies on ourplanet. Antarctic lakes are usually depauperate sys-tems and are characterized by truncated microbi-ally dominated food webs. Moreover, unlike manylakes at lower latitudes that suffer the direct im-pacts of Man's industrial and agricultural activities,Antarctic lakes are pristine. However, they are sub-ject to the indirect anthropogenic effects of globalclimate change and enhanced UV radiation. Polarlakes, both in the Arctic and Antarctic, are widelyrecognized as sentinels of local and global climatechange. We have not included a specific chapter onthis important issue, but embedded informationthroughout the book.

Ice is an important factor in polar limnology.Lakes are either covered by it, in the case of sub-glacial lakes by up to a 4 km thickness, or they arelocated on glaciers or ice shelves. Within Antarcticlakes research traditional limnologists have workedwith glaciologists, and the boundary between whatwere traditionally two distinct disciplines hasblurred. The study of Antarctic lakes exemplifiesthe need for a multi-disciplinary approach which isparticularly well illustrated by the McMurdo LongTerm Ecosystem Research Program.

We are indebted to colleagues and friends world-wide who have kindly given us access to their pho-tographs. We thank our editors Ian Sherman andLucy Nash and the many other people who havecontributed to the production of this volume. Par-ticular thanks go to Simon Powell at Bristol Uni-versity for his excellent work on the illustrations.Lastly we would like to thank the US, Australian,New Zealand, and British Antarctic programmesand acknowledge funding from a wide range Ofbodies, both national and international, thPF\In August 2001, Gary Comer, the transoceanic sailor who founded the Lands'End direct mail clothing empire and who had been fascinated with the Arcticsince childhood, successfully completed a voyage from Greenland through theNorthwest Passage. For centuries mariners had tried to navigate through ice-choked channels of the Northwest Passage that connect the Atlantic and Pacificoceans at the top of the world. Even the names of these channels conjure up theimages of the men and their sponsors who tried and mostly failed to find aroute through this treacherous Northwest Passage—Franklin Bay, Peel Sound,Prince Regent Inlet, Coronation Gulf, Amundsen Gulf, and the Beaufort Sea.

Comer's was the first private voyage through this legendary passage com-pleted in a single season without the services of a government icebreaker—andthe fastest in history, completing the crossing in sixteen days and eight hours.That accomplishment changed his life and set the stage for his decision to fundimportant scientific research that has altered our understanding of the globalextent of abrupt climate change.

Although Comer was thrilled by the unexpected success of the expedition, herecognized that the rapid melting of the sea ice that enabled him to completehis voyage presaged massive environmental changes to the Arctic. Shortly aftercompleting his historic journey, Comer sold Lands' End and was free from alifetime of business responsibilities. A modest, self-effacing man who had goneto work to support himself after high school, Comer began visiting scientistsaround the United States and asking them to instruct him on how the changeshe had witnessed in the Arctic would affect the rest of the world, since he sensedthat the region might be a distant early-warning area for the effects of globalwarming.

I had been aboard various expeditions with Gary Comer to remote parts of thenorthern oceans, informally assigned the role of expedition naturalist aboard his152-foot vessel, Turmoil. After Comer's successful crossing of the Northwest Pas-sage in 2001, I suggested he contact Wallace "Wally" Broecker, an oceanographerat Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. From background reading, I knew that Broecker had spent a half-century studying how oceans andthus climates have swung back and forth between warm and cold phases in theearth's geologic past and that he was the recipient of numerous awards, includ-ing the Crafoord Prize, the "Nobel Prize" for scientific fields lacking a Nobel.When they met at Broecker's lab, he told Comer of the recent scientific discov-eries that showed how abruptly climate had changed in the past and describedhis concern for the unpredictable effects that future climate change representsto life on the planet as we know it.

In the absence of any significant leadership in Washington at the time tofund a coordinated abrupt climate change program, Comer decided to fund amajor effort himself and asked Broecker to help organize an interdisciplinaryprogram to recruit talented young scientists to improve the understanding ofthis field of research.

Both iconoclasts in their own areas of endeavor, Comer and Broecker hitit off immediately. In Broecker, Comer found a world-class intellect, a scientistwith blunt opinions and a respected antibureaucratic nature that reflectedComer's own deepest inclinations. Under Broecker's guidance, Comer beganinvesting tens of millions of dollars to work with a network of the most distin-guished scientific mentors in the world to identify promising young PhD candi-dates and newly minted post-doctoral students to track changes in the earth'socean and atmospheric systems across the globe. Broecker quickly recruitedGeorge Denton, a geologist from the University of Maine, and Richard Alley, aglaciologist from Penn State, to help coordinate the Comer Fellows Program inAbrupt Climate Change Research.

During the Arctic summers of 2002, 2003, 2005, and 2006 Comer, Broecker,Denton, Alley, and their students organized a series of research expeditions tothe Arctic, and in particular to Greenland, while Comer also battled cancer, whichultimately claimed him in 2006. Comer invited scientists to travel aboard theTurmoil, to identify sites for further field research. We traveled widely through-out vast areas of the Arctic, including several voyages to western, southern, andeastern Greenland. With Turmoil's cruising range of 10,000 miles, accompaniedby either an amphibious float plane or a helicopter that could land on Turmoil'safterdeck, the scientists had undreamed-of access to nearly any site they wantedto visit from the western Canadian Arctic to eastern Greenland. Comer, a highlytalented photographer in his own right, documented these expeditions.

By 2003, under the banner of the Comer Fellowship Program, Broecker,Denton, and Alley had established a network of 25 senior scientists to focus onthe global dynamics of abrupt climate change. With the commitment of sig-nificant multiyear funding, Broecker, Denton, and Alley fashioned a scientificprogram to blend both model-based and paleoclimatic approaches to under-standing climate change, with one important caveat: they focus on the studyof changes in the earth's climate that occur not slowly over tens of thousandsof years, but over periods of decades or years.

What Gary Comer's support has accomplished in the most profound senseis to have helped scientists who study abrupt climate change to understand moreof the risks we face and encourage a prudent response. Like a venture capitalist,Comer found the people with big ideas and small means, relying on Broecker,Denton, and Alley to find the brightest young scientists at the beginning of theircareers to focus on the big questions rather than on fund-raising at a criticalpoint in their careers. Because Comer was the "venture capitalist," these efforts arenot isolated from the broader scientific community, but rather are the frameworkon which the broader scientific community is building. The venture capitalistinvests in the hope of greater riches. Comer had already been wildly successfulin the business world, and then invested for a much bigger payoff, to change howwe understand the world.at hassupported our own research in Antarctica.

查看更多

目录

Preface ix

Acknowledgments xv

Introduction: Lessons from Abrupt Climate Change 1

1 Mystery of the Ice Ages 25

2 Rosetta Stones from the Greenland Ice Sheet 47

3 A Role for All Seasons 75

4 Ihe Great Ocean Conveyor 101

5 A Wobbly North Atlantic Conveyor? 121

6 Greenland's Climate Signal across the Globe 147

7 Carbon Dioxide and the Fate of the Greenland Ice Sheet 165

8 Out of the Ice: The Lessons from Greenland 183

Bibliography 205

Index 211

查看更多

馆藏单位

中科院文献情报中心